Why in news?

- India’s ranking on the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) improved by one position in 2022 to 134 out of 193 countries ranked compared to 135 out of 191 countries in 2021.Switzerland has been ranked number one.

What’s in today’s article?

- Human Development Index (HDI)

- Key highlights of the Human Development Report (HDR)2023/24

- Observations made by the HDR 2023/24

- Four areas for immediate action proposed by the report

The Human Development Index (HDI)

- About

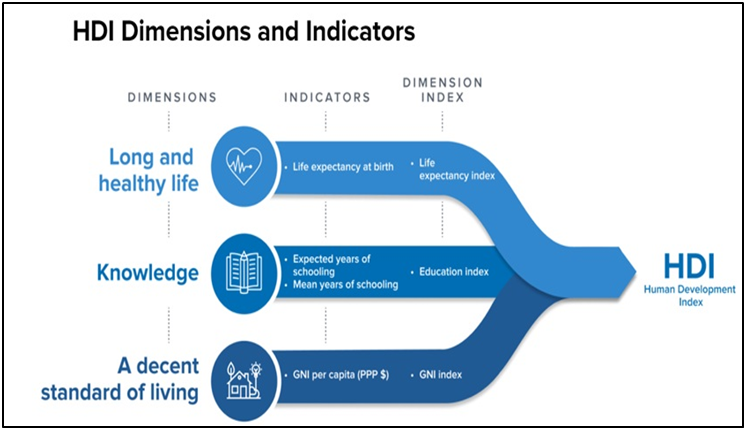

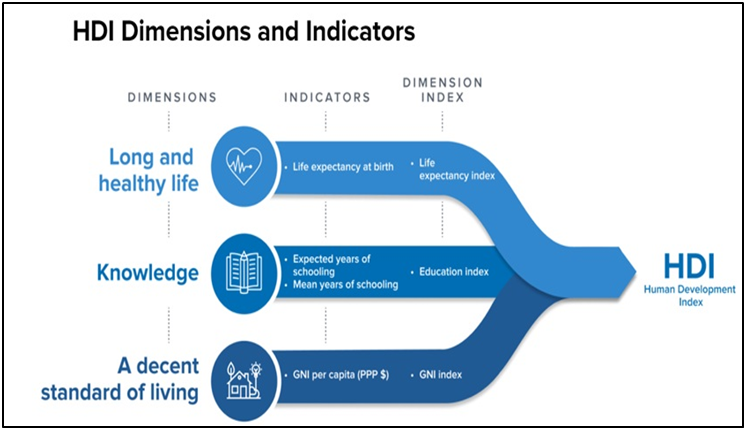

- It is a statistical composite (first published in 1990 by the UNDP) index, which measures average achievement of a country in 3 basic dimensions –

- Background

- It was developed by Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq and is now used to assess a country’s development as part of the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Report.

- Along with HDI, HDR also presents:

- Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI),

- Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI),

- Gender Inequality Index(GII) since 2010 and

- Gender Development Index (GDI) since 2014.

- Th HDI also embodies Amartya Sen’s “capabilities” approach to understand human well-being, which emphasizes the importance of ends (like a decent standard of living) over means (like income per capita).

Key Highlights of the HDR 2023/24 – India specific

- Theme of the report

- Recently released 2023/24 Human Development Report (HDR) was titled as “Breaking the Gridlock: Reimagining Cooperation in a Polarized World.”

- India’s ranking

- India ranked 135 in 2021. It had moved up to 134 in 2022.

- India in the medium human development category

- Between 1990 and 2022, the country saw its HDI value increase by 48.4 percent, from 0.434 in 1990 to 644 in 2022.

- India’s performance on various indicators

- India’s life expectancy at birth has slightly improved from 67.2 years in 2021 to 67.7 years in 2022.

- There is an overall increase (5.88%) in expected years of schooling (EYS) from 11.9 years to 12.6 years, leading to an improvement of 18 places.

- Gross National Income (GNI) per capita also improved from $6,542 to $6,951.

- Performance of India’s neighbourhood

- Sri Lanka has been ranked much ahead at 78, while China is ranked 75, both categorised under the High Human Development category.

- Bhutan stands at 125 and Bangladesh at 129th position.

- Nepal (146) and Pakistan (164) have been ranked lower than India.

- India’s progress in reducing gender inequality

- India has also shown progress in reducing gender inequality and ranks 108 out of 166 countries in the Gender Inequality Index (GII) 2022.

- The GII measures gender inequalities in three key dimensions – reproductive health, empowerment, and labour market.

- The country’s GII value of 0.437 is better than the global average of 0.462 and the South Asian average of 0.478.

- India’s performance in reproductive health is better than other countries in the medium human development group or South Asia.

- India’s adolescent birth rate in 2022 was 16.3 (births per 1,000 women ages 15-19), an improvement from 17.1 in 2021.

- However, India also has one of the largest gender gaps in the labour force participation rate—a 47.8 percentage points difference between women (28.3%) and men (76.1%).

Observations made by the HDR 2023/24

- The report shows that the two-decade trend of steadily reducing inequalities between wealthy and poor nations is now in reverse.

- The failure of collective action to advance action on climate change, digitalisation or poverty and inequality not only hinders human development but also worsens polarisation and further erodes trust in people and institutions worldwide.

- Nine in 10 people worldwide endorse democracy, but over half of the respondents expressed support for leaders who may undermine it, for instance, by bypassing fundamental rules of the democratic process.

- Political polarisation in countries is also responsible for protectionist or inward-turning policy approaches.

Four areas for immediate action proposed by the report

- To break through the current deadlock & reignite a commitment to a shared future:

- planetary public goods for climate stability as we confront the unprecedented challenges of the Anthropocene;

- digital global public goods for greater equity in harnessing new technologies for equitable human development;

- new and expanded financial mechanisms, including a novel track in international cooperation that complements humanitarian assistance and traditional development aid to low-income countries; and

- dialling down political polarization through new governance approaches focused on enhancing people’s voices in deliberation and tackling misinformation.

CAA’s Legal Issues & Status of Judicial Proceedings

Why in News?

- Four years after the Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) notified the rules to implement the law on March 11.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Background (About CAA, Provisions, etc.)

- Constitutional Validity (w.r.t. Article 14, Judicial Status, Section 6A, etc.)

Background:

- The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 fast-tracks citizenship to undocumented immigrants from six non-Muslim communities from the neighboring Muslim countries of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh.

- The six non-Muslim communities are Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Parsi, Christian and Jain.

- As per the rules of the Act, the applicants must provide certain documents and specify date of entry in India to be eligible for citizenship. The cutoff date for entry is December 31, 2014.

- Although the Act was passed on December 11, 2019, and received assent from the President on December 12 of the same year, it could not be implemented since the rules were not framed.

- The Act is under challenge before the Supreme Court, with several petitioners moving fresh pleas seeking a stay on the implementation of the rules.

Violation of Article 14 of the Constitution:

- Immediately after the passage of the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2019, the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) filed a petition in the Supreme Court challenging its constitutionality.

- These petitions primarily challenge the law for violating Article 14 of the Constitution which guarantees all ‘persons’ (not only citizens) equality before the law and equal protection of law.

- They also argue that making religion a qualifier for citizenship violates secularism, which is a basic feature of the Constitution.

- The petitioners have contended that the special treatment given to the specific persecuted religious minorities from the three Muslim-majority neighboring countries does not constitute a reasonable classification under Article 14.

- More so because groups like the Tamil Hindus in Sri Lanka, the Rohingyas in Myanmar and minority Muslim sects like the Hazaras in Afghanistan also face persecution but have been denied similar protection under this law.

- The CAA has also been dubbed as a move to subvert the Assam Accord of 1985 that deems any person who cannot prove his ancestry beyond March 24, 1971, an alien and does not differentiate on grounds of religion.

- The petitions, especially one by the All-Assam Students’ Union, contend that the law will further multiply the uncontrolled influx of illegal migrants from Bangladesh to Assam.

Central Government’s Response:

- The Centre in its affidavit before the Supreme Court said that it seeks to provide amnesty to specific communities from specified countries with a clear cut-off date.

- It highlighted that the law does not in any manner affect the legal, democratic or secular rights of any Indian citizen.

- The affidavit further stated that the narrowly tailored legislation was passed to tackle a specific problem, i.e., the persecution on the ground of religion in the light of the undisputable theocratic constitutional position in these specified countries.

- It added that in matters of foreign policy, citizenship, and economic policy among others, a wide latitude is available to the Parliament.

Judicial Status of the CAA:

- On December 18, 2019, a Bench comprising former Chief Justice of India (CJI) S.A. Bobde, Justices B.R. Gavai and Surya Kant refused to stay the operation of the law.

- They instead suggested that the government publicise the actual intent of the Act so that there was no confusion among the public about its objectives and aims.

- On October 6, 2022, a Bench comprising former CJI U.U. Lalit and Justices Ravindra Bhat and Hima Kohli passed an order stating that final hearings in the case would begin on December 6, 2022.

- However, the case has not been listed since then.

- As per the Supreme Court’s website, the petitions are currently listed before a Bench headed by Justice Pankaj Mithal.

Relation with Section 6A of the Citizenship Act:

- The proceedings against the CAA are also dependent on the outcome of the challenge to Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955.

- The section was introduced in furtherance of a Memorandum of Settlement called the “Assam Accord” signed on August 15, 1985, between the Centre and the leaders of the Assam movement.

- Section 6A determines who is a foreigner in Assam by establishing March 24, 1971, as the cut-off date for entry. Those entering the state after that would be considered “illegal immigrants”.

- Those who came to the State on or after January 1, 1966, but before March 25, 1971, were to be declared as “foreigners” and would have all the rights and obligations of Indian citizens except for being included in electoral rolls for 10 years.

- If March 24, 1971, is upheld as a valid cut-off date for entry into the State, then CAA can be held to be violative of the Assam Accord since it establishes a different timeline.

How did Indians End Up in the Russia-Ukraine War

Why in News?

- The deaths of two Indian nationals in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war illustrate the plight of dozens of Indians trapped on the front lines after being duped into working with the Russian military.

- Also, recent CBI raids found a human trafficking network recruiting Indians as security helpers and other personnels for the Russian military, have sparked widespread concern.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- What Happened with Indians in Russia?

- How did the Agents Deceive People?

- What has the Indian Government Said?

What Happened with Indians in Russia?

- A series of reports brought attention to the situation that some Indian nationals, initially hired as army security helpers, were compelled to fight against their will after their passports and documents were seized.

- According to a resident of Uttar Pradesh, he went to Russia with the help of an agent in November last year.

- They were assured that they would not be sent to the battlefield and offered a monthly pay of ₹1.95 lakh with an additional ₹50,000 incentive.

- However, they were sent to the frontline in January (2024) after some basic training in handling weapons.

- An Indian-origin Russian official associated with the Russian Ministry of Defence told that approx. 100 Indians were recruited at the Moscow recruitment centre in the past year.

- However, the actual number of Indians hired could be higher, since there are several recruitment centres across Russia.

How did the Agents Deceive People?

- A multi-State human trafficking network busted by the CBI in a crackdown on visa recruiters in seven cities across India revealed how Indian youths were allegedly pushed into the war zone by consultancy firms.

- The Indian youths were duped on the pretext of a better life and livelihood with the Russian military as security guards and helpers, as well as higher education.

- As per the CBI, the “organised network” lured Indian youth through social media and local agents, offering them highly paid jobs and lucrative employment opportunities in Russia.

- A number of students were reportedly tricked into enrolling in dubious private universities by agents promising low fees and visa extensions.

- Once the aspirants reached Russia, the local agents seized their passports and forced them to join the armed forces.

What has the Indian Government Said?

- The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) has issued warnings (last month) to Indian citizens about the dangers of being recruited for support roles in the Russian army.

- The Indian government is in talks with the Russian authorities about the early release of Indian citizens who were duped into working with the Russian military.

- Noting the findings of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) raids, the MEA appealed to Indian nationals not to be swayed by offers made by agents for support jobs with the Russian Army.