Chapter 21 : Advent of Europeans in India

Introduction

- The history of modern India may be traced back to the advent of Europeans to India. The trade routes between India and Europe were long and winding, passing through the Oxus Valley, Syria, and Egypt. Trade increased after Vasco da Gama discovered a new sea route via the Cape of Good Hope in 1498, and many trading companies came to India to establish trading centres. Gradually all European superpowers of the contemporary period the Dutch, English, French, Danish etc established their trade relations with the Indian Subcontinent.

- In the late fifteenth century, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama reached the shores of the Indian subcontinent, establishing maritime connections that marked the onset of European influence. Subsequent expeditions by other European powers, including the Dutch, English, and French, intensified this engagement, leading to competition for trade dominance and territorial control.

- The establishment of trading posts and colonies paved the way for a new chapter in India’s history, shaped by global interactions and the eventual ascendance of British colonial rule. The arrival of Europeans would indelibly shape India’s destiny and leave a lasting imprint on its social, economic, and political landscapes.

The Advent of Europeans in India

The advent of Europeans in India marked a significant turning point in the history of India.

- The arrival of Vasco da Gama: It began with the arrival of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in 1498, establishing a direct sea route between Europe and India. This pivotal moment opened doors to European colonialism and trade domination in the sub-continent.

- Other Europeans: The Portuguese, followed by other European powers, sought to control the lucrative spice trade, leading to the establishment of trading posts and fortifications along the Indian coastline.

- Impact: Their arrival brought about cultural exchanges, conflicts with local rulers, and the reshaping of Indian society. This period laid the foundation for centuries of European influence and colonial rule in India.

The Advent of The Portuguese

- The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive in India, and they were also the last to go.

- The spirit of the Renaissance, with its demand for adventure, captivated Europe in the fifteenth century.

- During this time, Europe achieved significant breakthroughs in shipbuilding and navigation. As a result, there was a strong desire throughout Europe for daring maritime trips to the East’s unexplored reaches.

Factors behind the Portuguese Voyage to India

After the decline of the Roman Empire and the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Arabs established dominance in Egypt and Persia, controlling the trade routes to India. The Europeans lost direct contact with India and the easy accessibility to Indian commodities.

- Spirit of the voyage: In the 15th century, there was a growing eagerness in Europe for adventurous sea voyages to reach the East, driven by the spirit of the Renaissance and advancements in shipbuilding and navigation.

- Division of non-Christian world: The Treaty of Tordesillas(1494) divided the non-Christian world between Portugal and Spain, granting Portugal the eastern territories and Spain the western territories. This set the stage for Portuguese incursions into the waters around India.

Discovery of a Sea Route to India

- Historians have noted that discovering an ocean route to India had become an obsession for Prince Henry of Portugal, known as the ‘Navigator,’ as well as a method to sidestep the Muslim dominance of the eastern Mediterranean and all the roads connecting India and Europe.

- The kings of Portugal and Spain split the non-Christian world between them in 1497, under the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), by an imaginary line in the Atlantic, about 1,300 miles west of the Cape Verde Islands.

- Portugal could claim and occupy anything to the east of the line, while Spain could claim everything to the west, according to the pact.

- As a result, the scene was set for Portuguese intrusions into the Indian Ocean seas.

- Bartholomew Dias, a Portuguese navigator, crossed the Cape of Good Hope in Africa in 1487 and travelled along the eastern coast, believing that the long-sought maritime path to India had been discovered.

- However, an expedition of Portuguese ships set off for India barely 10 years later (in 1497) and reached India in little less than 11 months, in May 1498.

The Portuguese Governors

- Vasco da Gama:

- The arrival of Vasco da Gama in Calicut (now Kozhikode) in 1498 had a significant impact on Indian history. The Hindu ruler of Calicut, the Zamorin, welcomed him as the prosperity of his kingdom relied on trade.

- The landing of three ships under Vasco Da Gama to Calicut in May 1498, headed by a Gujarati pilot called Abdul Majid, had a significant impact on Indian history.

- However, the Arab traders, who had a strong presence on the Malabar coast, were concerned about the Portuguese gaining influence in the region.

- The Portuguese aimed to monopolise the profitable eastern trade and exclude their competitors, especially the Arabs.

- At Cannanore, Vasco da Gama established a trading factory.

- Calicut, Cannanore, and Cochin gradually became key Portuguese commerce centres.

- Vasco da Gama returned to India in 1501 but faced resistance from the Zamorin when he sought to exclude Arab merchants in favour of the Portuguese.

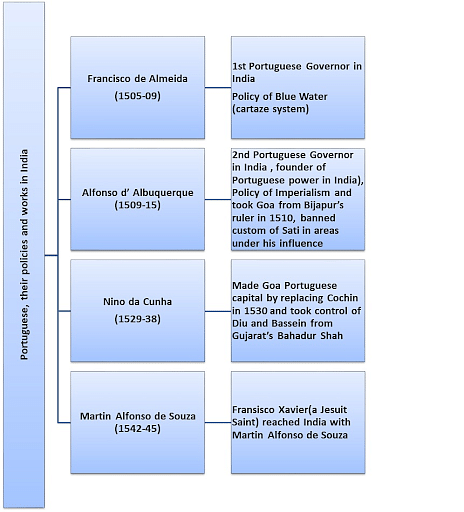

- Francisco de Almeida (1505-1509):

- In 1505, Francisco de Almeida was appointed as the Governor of India, with the mission to consolidate Portuguese influence and destroy Muslim trade.

- Almeida faced opposition from the Zamorin and a threat from the Mamluk Sultan of Egypt.

- In 1507, the Portuguese squadron was initially defeated in a naval battle off Diu but avenged the defeat the following year.

- Almeida aimed to make the Portuguese the masters of the Indian Ocean through his Blue Water Policy.

- Blue Water Policy (Cartaze system): It was a naval trade licence or pass issued by the Portuguese empire in the Indian Ocean during the sixteenth century. Its name derives from the Portuguese term ‘cartas‘, meaning letters.

- In 1505, Francisco de Almeida was appointed as the Governor of India, with the mission to consolidate Portuguese influence and destroy Muslim trade.

- Alfonso de Albuquerque (1509-1515)

- Alfonso de Albuquerque succeeded Almeida and established Portuguese bases strategically overlooking the entrances to the Indian Ocean.

- Albuquerque introduced a permit system for other ships and exercised control over major shipbuilding centres.

- Goa was acquired from the Sultan of Bijapur in 1510, becoming the first Indian territory under European control since Alexander the Great‘s time.

- Albuquerque’s rule also saw Portuguese men settling in India, establishing themselves as landlords, artisans, craftsmen, and traders.

- An interesting feature of his rule was the abolition of sati.

- Nino da Cunha (1529-1538)

- He moved the headquarters from Cochin to Goa.

- The Portuguese secured the island of Bassein and its dependencies from Bahadur Shah of Gujarat in 1534, but their relations soured after Humayun withdrew from Gujarat, leading to a confrontation in which Bahadur Shah was killed by the Portuguese in 1537.

- Additionally, da Cunha attempted to increase Portuguese influence in Bengal by settling many Portuguese nationals there with Hooghly as their headquarters.

Decline of the Portuguese

By the 18th century, the Portuguese in India experienced a decline in their commercial influence.

- The Portuguese lost their local advantages as powerful dynasties emerged in Egypt, Persia, and North India, and the Marathas became their immediate neighbours.

- The Marathas captured Salsette and Bassein from the Portuguese in 1739.

- The religious policies of the Portuguese, including the activities of the Jesuits, caused political concerns.

- Their conversion efforts to Christianity, coupled with antagonism towards Muslims, led to resentment among Hindus.

Significance of the Portuguese

- The emergence of naval power: The arrival of the Portuguese in India marked the emergence of naval power and initiated what is often referred to as the European era.

- Own systems: The Portuguese disregarded existing rules and sought to establish their dominance over Indian trade and the Indian Ocean trading system.

- Military innovations: In the sixteenth century Malabar, the Portuguese demonstrated military innovation with their use of body armour, matchlock men, and guns landing from their ships.

- Maritime techniques: The Portuguese excelled in maritime techniques, with their heavily constructed multi-decked ships designed to withstand Atlantic gales, allowing for heavier armament.

- Organisational skills: Their organisational skills, the establishment of royal arsenals and dockyards, and the maintenance of a regular system of pilots and mapping were notable contributions.

- Religious Policy: The Portuguese arrived in the East with a zeal to promote Christianity and persecute Muslims. They were initially tolerant towards Hindus but became increasingly intolerant over time, especially after the introduction of the Inquisition in Goa.

Portuguese Administration in India

- The Bahmani Kingdom in the Deccan was dissolving into smaller kingdoms.

- None of the powers possessed a fleet worth mentioning, and they had no plans to improve their maritime capabilities.

- The Chinese emperor’s imperial proclamation limited the nautical reach of Chinese ships in the Far East.

- The Arab merchants and shipowners who had previously controlled the Indian Ocean commerce had nothing on the Portuguese in terms of organisation and cohesiveness.

- The Portuguese also had guns mounted on their ships.

- The viceroy, who ruled for three years, was in charge of the administration, together with his secretary and, subsequently, a council.

- Next insignificance was the Vedor da Fazenda, who was in charge of income, cargoes, and fleet dispatch.

Portuguese, their Policies and Works in India

The Advent of The Dutch

- Under the name Vereenigde Oost Indische Compagnie (VOC), the Dutch East India Company was founded about 1602 CE.

- The Dutch established their first facility at Masulipatnam, Andhra Pradesh. They also created commercial terminals in Gujarat (Surat, Broach, Cambay, and Ahmedabad), Kerala (Cochin), Bengal (Chinsurah), Bihar (Patna), and Uttar Pradesh (Agra).

- Their major base in India was Pulicat (Tamil Nadu), which was subsequently superseded by Nagapattinam.

- They defeated the Portuguese in the 17th century and became the most powerful force in European commerce in the East.

- They expelled the Portuguese out of the Malay straits and the Indonesian islands and thwarted English attempts to settle there in 1623.

The Dutch Commercial enterprise led them to undertake voyages to the East.

- Trading company: In 1602, the States-General of the Netherlands merged various trading companies to form the East India Company of the Netherlands.

- This company was granted the authority to conduct wars, negotiate treaties, acquire territories, and establish fortresses.

- Trading centre: The Dutch established their control over Masulipatnam in 1605 and they established their settlement at Pulicat in 1610.

Anglo-Dutch Rivalry

- The English were also gaining importance in the Eastern trade at this time, posing a severe threat to the Dutch economic interests.

- The commercial competition quickly devolved into bloodshed.

- After years of fighting, both parties reached an agreement in 1667, in which the British promised to relinquish all claims to Indonesia and the Dutch agreed to leave India to focus on their more successful commerce in Indonesia.

- They had a monopoly on the black pepper and spice trade. Silk, cotton, indigo, rice, and opium were the most significant Indian goods sold by the Dutch.

- Also, the Anglo-Dutch competition lasted around seven years, during which time the Dutch lost one by one their colonies to the British until the Dutch were eventually beaten by the English in the Battle of Bedara in c. 1759.

The Decline of Dutch in India

- The English retaliation ended in the Dutch being defeated in the Battle of Hooghly (November 1759), thereby ending Dutch ambitions in India.

- The Dutch were not interested in establishing an empire in India; their main focus was trade.

- In any event, their major economic interest was in the Indonesian Spice Islands, from which they made a large profit.

The Advent of The English

- The English Association or Company to Trade with the East was founded about 1599 CE by a group of merchants known as “The Merchant Adventurers.”

- Queen Elizabeth granted the corporation a royal charter and the exclusive right to trade in the East on December 31, 1600 CE, and it became known as the East India Company.

The Rise of English

- Captain William Hawkins landed at the court of Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1609 CE to request permission to open an English trading post in Surat.

- The Emperor, however, declined it owing to Portuguese pressure.

- Later, in 1612 CE, Jahangir gave the East India Company permission to build a factory at Surat.

- Sir Thomas Roe arrived at the Mughal court as an envoy for James I, King of England, in c. 1615 CE and was successful in obtaining an Imperial Farman to trade and develop factories in various regions of India.

- The English developed factories in Agra, Ahmedabad, Baroda, and Broach by c. 1619 CE.

- Masulipatnam was the site of the English’s first factory in the south.

- Francis Day bought Madras from the Raja of Chandragiri in 1639 CE and erected a modest fort around their factory called Fort St. George.

- On the Coromandel coast, Madras quickly displaced Masulipatnam as the English headquarters.

- In c. 1668 CE, the English East India Company purchased Bombay from Charles II, the then-king of England, and Bombay became the company’s west coast headquarters.

- Job Charnock founded an English workshop in a region named Sutanuti in 1690 CE.

- It ultimately became the city of Calcutta, which was home to Fort William and later became the capital of British India.

- British towns in Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta grew into thriving metropolises.

- As the British East India Company expanded in prominence, it was on the verge of becoming a sovereign state in India.

- An English mission headed by John Surman to the Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar’s court in 1715 gained three notable farmans, granting the Company numerous important rights in Bengal, Gujarat, and Hyderabad.

In 1599, a group of English merchants known as the ‘Merchant Adventurers‘ formed a company to pursue Eastern trade and share in the high profits enjoyed by the Portuguese.

- Queen’s charter: Queen Elizabeth I issued a charter on December 31, 1600, granting exclusive trading rights to the newly formed ‘Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies.’

- Initially granted a monopoly of fifteen years, it was later extended indefinitely.

Foothold in West and South

- Arrival at Jahangir’s court: In 1609, Captain Hawkins arrived at the court of Jahangir in an attempt to establish a factory at Surat, but it was unsuccessful due to Portuguese opposition.

- Beginning of trade: However, the English began trading at Masulipatnam in 1611 and established a factory there in 1616.

- Battle with Portuguese: In 1612, Captain Thomas Best defeated the Portuguese in a sea battle of Surat, leading to Jahangir granting permission for an English factory in Surat in 1613.

- Peace was established with the Portuguese, and an Anglo-Dutch compromise allowed the English to trade without interference.

- Gift of Bombay: Bombay was gifted to King Charles II in 1662 and later given to the East India Company in 1668, becoming their headquarters in 1687.

- Madras: The English also obtained trading privileges from the Sultan of Golconda and built a fortified factory at Madras in 1639, which became the headquarters of English settlements in South India.

Foothold in Bengal

Bengal, a prosperous and significant province of the Mughal Empire, attracted English merchants due to its trade and commercial opportunities.

- Permission to trade: In 1651, Shah Shuja, the subahdar of Bengal, granted the English permission to trade in Bengal in exchange for an annual payment.

- Request for a fortified settlement: Seeking a fortified settlement, William Hedges, the first agent and governor of the Company in Bengal, appealed to Shaista Khan, the Mughal governor, but hostilities ensued.

- Settlement at Sutanuti: In 1686, Hooghly was sacked by the Mughals, leading to English retaliation. After negotiations, Job Charnock signed a treaty with the Mughals in 1690, allowing the English to establish a factory at Sutanuti.

- Fort William: The English obtained permission to buy the zamindari of Sutanuti, Gobindapur, and Kalikata in 1698, and the fortified settlement was named Fort William in 1700, becoming the seat of the eastern presidency (Calcutta).

The Advent of The French

- Colbert, a minister under Louis XIV, formed the French East India Company in 1664 CE.

- Francis Caron established the first French factory in Surat about 1668 CE. Maracara built a factory at Masulipatnam in 1669 CE.

- Francois Martin created Pondicherry (Fort Louis) in c. 1673 CE, which later became the seat of the French holdings in India, and he served as its first governor.

- The French took Chandranagore near Calcutta from the governor, Shaista Khan, in 1690 CE. At Balasore, Mahe, Qasim Bazar, and Karaikal, the French erected factories.

- The advent of French governor Joseph François Dupleix in India in around 1742 CE marked the start of Anglo-French warfare, which culminated in the legendary Carnatic wars.

Pondicherry – The Nerve Centre of French

- Francois Martin, the director of the Masulipatnam factory, was granted a location for a colony in 1673 by Sher Khan Lodi, the administrator of Valikandapuram (under the Bijapur Sultan).

- Pondicherry was established in the year 1674. Caron was succeeded as French governor by Francois Martin the next year.

- Other sections of India, notably the coastal regions, were also home to the French company’s plants.

- The French East India Company‘s commercial centres included Mahe, Karaikal, Balasore, and Qasim Bazar.

- Francois Martin established Pondicherry as a significant location after gaining command in 1674. It was, after all, the French’s bastion in India.

First Carnatic War (1740–48)

- The Anglo-French War in Europe was triggered by the Austrian War of Succession, and the First Carnatic War was a continuation of that conflict.

- The Treaty of Aix-La Chapelle, which brought the Austrian War of Succession to a close, concluded the First Carnatic War in 1748.

- Madras was returned to the English under the provisions of this treaty, while the French received their colonies in North America in exchange.

Second Carnatic War (1749–54)

- Dupleix, the French governor who had led the French armies to victory in the First Carnatic War, aspired to expand his authority and political influence in southern India by engaging in local dynastic rivalries to beat the English.

- The English and the French agreed not to intervene in native rulers’ quarrels.

- Furthermore, each side was left in control of the territory that they had occupied at the time of the pact.

- It became clear that Indian authority was no longer required for European success; rather, Indian authority was growing increasingly reliant on European backing.

Third Carnatic War (1758–63)

- When Austria attempted to reclaim Silesia in 1756, the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) broke out in Europe.

- Once again, the United Kingdom and France were on opposing sides.

- The Treaty of Peace Paris (1763) restored the French industries in India, but after the war, French political dominance vanished.

- The Dutch having already been beaten in the Battle of Bidara in 1759, the English became the dominant European force on the Indian subcontinent.

English Success and the French Failure – Causes

- The English company was a private enterprise, which instilled in the people a sense of pride and self-assurance.

- The French company, on the other hand, was a government-owned enterprise.

- The French government-controlled and regulated it, and it was boxed in by government policies and decision-making delays.

- The English navy was superior to the French fleet, and it assisted in cutting off the important maritime route between France and its Indian colonies.

- Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras were all under English control, whilst Pondicherry was under French control.

- The French prioritised territorial ambition over business interests, leaving the French enterprise cash-strapped.

The Advent of The Danes

- In 1616, the Danish East India Company was created, and in 1620, they opened a factory in Tranquebar, near Tanjore, on India’s eastern coast.

- Serampore, near Calcutta, was their main settlement. In 1845, the Danish industries were sold to the British government, despite the fact that they were unimportant at the time.

- The Danes are better recognised for their missionary work than for their commercial endeavours.

English Success against Other European Powers

- The English East India Company, which was founded by the merger of many rival firms at home, was governed by a board of directors whose members were chosen on an annual basis.

- The state held a substantial portion of France’s and Portugal’s commercial firms, and their character was feudalism in many aspects.

- The Royal Navy of Britain was not only the largest but also the most technologically sophisticated at the time.

- The industrial revolution arrived late in other European countries, allowing England to preserve its dominion.

- The British soldiers were well-trained and disciplined. The British commanders were thinkers who experimented with novel military techniques.

- In comparison to Spain, Portugal, and the Dutch, Britain was less religiously passionate and eager in spreading Christianity.

- The Bank of England, the world’s first central bank, was formed to sell government debt to money markets on the promise of a fair return if Britain defeated competing countries such as France and Spain.