Editorials & Articles – 21 Feb 2024

Editorials & Articles – 21 Feb 2024

Having Panchayats as self-governing institutions.

| Context |

|

Background:

- 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments Acts in 1992 empowered local bodies for self-governance in India.

- Ministry of Panchayati Raj formed in 2004 to strengthen rural local governments.

Fiscal Devolution:

- Some states have excelled, while others lag in devolution commitment.

- Constitutional amendment emphasizes fiscal devolution, including own revenue generation.

Current Revenue Status:

- Panchayats earn only 1% through taxes; 80% from the Centre and 15% from States.

- Despite 30 years of devolution, revenue raised remains meager.

Own Source of Revenue (OSR):

- State Panchayati Raj Acts provide for taxation and non-tax revenue.

- Major own source of revenue (OSRs): Property tax, land revenue cess, stamp duty surcharge, tolls, profession tax, advertisement tax, user charges for services.

Expert Committee Report:

- Expert committee details OSR possibilities, including fees, rent, and income from investments.

- Recommends creating a conducive environment for effective taxation.

Role of Gram Sabhas:

- Gram sabhas crucial for local self-sufficiency and sustainable development.

- They have been empowered for planning, decision-making, and implementing revenue initiatives.

- Authority to impose taxes, fees, and levies for local development projects.

Discrepancies in Tax Collection:

- Inequitable tax collection responsibilities among gram, intermediate, and district panchayats.

- Gram panchayats collect 89%, intermediate 7%, and district panchayats only 5%.

Factors Hindering Revenue Generation:

- Central Finance Commission grants contribute to reduced interest in OSR.

- Dependency on grants increases, and tax collections decrease over time.

- Lack of incentivisation and penalties for defaulters.

Overcoming Dependency:

- Challenges include a societal ‘freebie culture’ and reluctance to impose taxes.

- Need for educating elected representatives and the public on the importance of revenue generation.

- Gradual reduction of dependency on grants for sustained self-sufficiency.

Future Recommendations:

- Dedicated efforts needed at all governance levels, including state and central, to minimize dependency syndrome.

- Panchayats should strive towards self-sufficiency through consistent revenue-generation initiatives.

Conclusion:

- Despite constitutional provisions, challenges persist in achieving meaningful fiscal devolution and self-sufficiency at the grassroots level.

- Education, incentivization, and consistent efforts are crucial for promoting local self-governance in India.

The real threat to the India as we know it

Introduction:

- The conclusion of the 17th Lok Sabha sets the stage for the upcoming general election.

- The final parliamentary session reflects increased divisiveness, raising concerns about the future of Indian parliamentary democracy.

Constitutional Safeguards:

- India, with a robust Constitution, Fundamental Rights, Duties, and Directive Principles, has sustained democracy.

- Current decline in parliamentary practices sparks worries about Parliament’s ability to maintain stable democracy.

Global and Internal Dynamics:

- External factors like global tensions (Ukraine, West Asia) and concerns about China exist but don’t pose immediate threats.

- Internal issues, like security concerns and regional conflicts, are manageable but require attention.

Political Division:

- Nation appears more divided than before, with accusations and vitriol between the ruling party and the opposition.

- The government cites the Opposition creating a “North-South Divide” and promoting divisive language.

Impact of Polarized Politics:

- On the verge of a critical election, polarized politics exacerbates divisive tendencies.

- Issues like the Ram Temple consecration become election points, contributing to a perceived Hindu majoritarianism.

Federalism Concerns:

- Federalism, a constitutional cornerstone, appears compromised with attempts like Uniform Civil Code and “One Nation, One Election.”

- Opposition accuses the ruling party of breaching federal principles, undermining regional parties.

Engineered Defections:

- Engineered defections, especially in an election year, challenge democracy and electoral integrity.

- Instances of high-level defections to the ruling party raise concerns about altering electoral verdicts by other means.

Governor’s Role and Centre-State Relations:

- Governors’ roles in Opposition-ruled states become contentious, leading to strained Centre-State relations.

- Perceived violations of constitutionally mandated conduct contribute to a breakdown in relations between the Centre and States.

Absence of Rules-Based Order:

- Lack of a rules-based order in Centre-State relations and party-to-party interactions poses dangers to the democratic system.

- Without adherence to constitutional principles, democracy under a constitutional mandate may cease to exist.

Need for Dispassionate Analysis:

- Onus lies mainly on the Centre, but both the ruling party and the Opposition need to uphold constitutional niceties.

- Tolerating differences, subordinating everything to the Constitution, and managing rivalries within constitutional boundaries are crucial.

Conclusion:

- A collapse of Constitution-mandated rules of business threatens democracy, emphasizing the need for dispassionate analysis and adherence to constitutional principles.

The minimum support

| Context: |

|

The Demand for Legalizing MSP: Understanding its Components:

- The farmers’ demand for MSP comprises two key elements.

- Firstly, they advocate for MSP to be set at the comprehensive cost of production (C2) as recommended by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), plus an additional 50% as suggested by the Swaminathan Commission.

- Secondly, they seek legal enforcement mandating that all crops covered under MSP are purchased at or above the MSP price by any market participant.

Quantifying the Impact of MSP Enforcement: Financial and Economic Considerations:

- The total value of the 23 crops covered under MSP for the year 2023-24 is estimated at around Rs 15 lakh crore.

- However, only a portion of this value reaches the markets due to various factors such as consumption, exchange within villages, and losses during harvesting and storage.

- Government purchase, combined with private sector procurement, falls significantly short of the total MSP value, with the private sector often paying below MSP rates.

- Enforcing MSP legally could potentially result in an additional financial outlay by the government, estimated at around Rs 1.5 lakh crore annually.

- However, this investment could stimulate economic growth through increased consumer spending, leading to higher demand, investment, and tax revenue.

Economic and Ecological Implications of Legal MSP:

- Enforcing MSP legally could incentivize crop diversification, leading to economic and ecological benefits.

- Farmers would no longer be compelled to focus solely on crops with MSP coverage, such as paddy, wheat, and sugarcane, thereby promoting diversification and better resource utilization.

- This could also lead to self-sufficiency in edible oils and pulses, reducing dependency on imports.

Addressing Concerns and Counterarguments:

- Some economists argue that enforcing MSP legally might discourage private sector participation in crop procurement.

- However, historical examples, such as sugarcane pricing, suggest otherwise, as government-prescribed prices haven’t deterred private mills from purchasing sugarcane.

- Additionally, MSP serves as a crucial safety net for farmers, ensuring their viability and thereby safeguarding food security.

Conclusion:

- The demand for a legal guarantee for MSP is not only justifiable but also crucial for ensuring the welfare of farmers and the stability of the agricultural sector.

- By providing a safety net for farmers, promoting crop diversification, and stimulating economic growth, legal MSP enforcement emerges as a win-win solution for all stakeholders.

- Ignoring this demand risks further unrest and threatens the livelihoods of millions of farmers, thereby underscoring the urgent need for decisive action by the central government.

| Why is There a Demand for Law on MSP? |

Ensuring Financial Viability of Agriculture:

Reducing Debt Burden on Farmers:

Supporting Farmers’ Livelihoods:

Risk Mitigation:

Addressing Market Imperfections:

Promoting Agricultural Growth:

Addressing Disparities:

|

Why are we falling ill so often?

| Context: |

|

Current Situation and Recommendations:

- The NCDC recommends heightened vigilance and testing for both influenza and COVID-19, given the increase in chest infections and hospital admissions.

- To combat the rising infections, the prudent use of the Southern Hemisphere’s 2024 quadrivalent influenza vaccine has been suggested.

- This vaccine targets the strains recommended by the World Health Organization for the current year, aiming to mitigate the spread of the virus.

Understanding Seasonal Influenza:

- Seasonal influenza, characterized by acute respiratory infections caused by influenza viruses, poses significant challenges globally.

- Its symptoms include fever, cough, headache, muscle and joint pain, sore throat, and runny nose, often leading to severe malaise.

- While most recover within a week, high-risk individuals, especially the elderly and children under five, face increased vulnerability to severe illness or death.

- In developing countries, the impact on children is particularly grave, with a majority of influenza-related deaths occurring in this demographic.

Factors Contributing to Influenza Transmission:

- Several factors contribute to the transmission of influenza in India, including high population density, poor hygiene practices, conducive weather conditions, and low vaccination rates.

- Extensive epidemiological studies have explored the interplay between respiratory virus epidemics and meteorological factors, with climate change emerging as a significant influencer.

- Shifts in temperature and rainfall patterns may alter the spatial and temporal dynamics of influenza outbreaks, exacerbating transmission risks.

Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment:

- Diagnosing influenza presents challenges, especially during periods of low activity when other respiratory viruses mimic its symptoms.

- Indiscriminate antimicrobial use, driven by the difficulty in clinical differentiation, further complicates treatment approaches.

- The misuse of antibiotics contributes to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a growing concern in India, necessitating interventions to curb excessive prescription practices.

Role of Vaccination and Immunization Programs:

- Vaccination remains a cornerstone in influenza control measures, with several countries, including India, recommending annual vaccination for high-risk groups.

- However, the inclusion of influenza vaccines in India’s Universal Immunization Programme is hindered by a lack of comprehensive data on morbidity and mortality associated with influenza.

- Leveraging the success of the COVID-19 vaccine program, there’s an opportunity to expand adult immunization efforts, potentially reducing community transmission and AMR-related challenges.

Conclusion:

- As India moves towards universal health coverage, addressing the growing burden of influenza requires a preventive approach, including the expansion of immunization programs.

- Prioritizing influenza prevention and control strategies can not only benefit vaccinated individuals but also contribute to reducing community transmission and associated complications.

- This proactive approach aligns with ongoing pandemic preparedness efforts and supports broader public health goals in the country.

| About National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) |

Major Functions

|

Why in news?

- The Supreme Court has quashed the result of the January 30 elections for the post of Mayor of the Chandigarh Municipal Corporation.

- The apex court declared the AAP-Congress candidate as the winner instead of the previously declared BJP candidate.

- The top court held that the presiding officer intentionally defaced eight votes, that were for the alliance candidate, to invalidate them.

- In overturning the results, the Supreme Court invoked the sweeping powers conferred on the court under Article 142 of the Constitution.

What’s in today’s article?

- Article 142 (Powers of SC under this article, Noticeable use, Controversies, Limitations)

Article 142

- About

- Article 142 provides a unique power to the Supreme Court, to do complete justice between the parties, where at times law or statute may not provide a remedy.

- In such instances, the Court can go beyond its usual limits to settle a dispute in a way that matches the specifics of the case.

- Powers of SC under this article

- The Art. 142 confers on the Supreme Court plenary power to pass such decree or make such order as is necessary for doing complete justice.

- The SC can do so in any cause or matter pending before it.

- Such orders of SC are enforceable throughout the territory of India as prescribed by any law made by Parliament or order of the President of India.

- Noticeable Use of Art. 142

- Union Carbide Corporation v. Union of India

- 142 remained unnoticed till the SC gave its decision in The Bhopal Gas Disaster Case.

- In this case, SC announced a settlement and stated that all civil proceedings wherever pending were concluded in terms of settlement.

- It quashed all criminal proceedings arising out of the disaster.

- In this case, the court ordered to award compensation to the victims and placed itself in a position above the Parliamentary laws.

- Babri Masjid Case

- The article was used in the Ram Janmabhoomi-Babri Masjid land dispute case and was instrumental in the handover of the disputed land to a trust to be formed by the union government.

- Manohar Lal Sharma v. Principal Secretary

- The Supreme Court can deal with exceptional circumstances interfering with the larger interest of the public in order to fabricate trust in the rule of law.

- Union Carbide Corporation v. Union of India

- Curative Petition – An Innovative use of Art 142

- The Supreme Court evolved the idea of curative petitions in the landmark judgment of Rupa Ashok Hurra vs. Ashok Hurra.

- The five-judge bench observed that Article 142 of the Constitution empowers the Supreme Court to act in whatever manner they may deem fit to establish complete justice.

- Therefore, to protect the substantive rights of the litigant, the Constitution Bench came up with the theory of a curative petition.

- Curative petition will be entertained on strong grounds only e.g.

- Violation of principles of natural justice.

- Where the judge has a bias

- It has to be certified by a senior advocate. If the bench finds that the petition is vexatious and without any merit it may impose exemplary costs on the petition.

- The Supreme Court evolved the idea of curative petitions in the landmark judgment of Rupa Ashok Hurra vs. Ashok Hurra.

- Controversies

- In R.S. Naik vs A. R. Antulay – SC, using Art 142, transferred cases against Antulay pending before the special judge to the High Court.

- In Vinay Chandra Mishra case – SC convicted Mishra for contempt of court.

- It was not proper for SC as the power to take disciplinary action is vested in the Bar Council under the Advocates Act.

- Cancellation of Coal Block Allocation – In 2014, the SC, using Art 142, cancelled the allocation of coal blocks granted from 1993 onwards.

- It was the domain of executive.

- Criticism

- On the grounds of separation of power

- Unlike the legislature and the executive, the judiciary cannot be held accountable for its actions.

- The power has been criticised on grounds of the separation of powers doctrine.

- Definition of complete justice

- It is further argued that the court has wide discretion due to the absence of a standard definition for the term complete justice.

- Defining complete justice is a subjective exercise that differs in its interpretation from case to case.

- On the grounds of separation of power

- Limitations on Art 142

- SC recognised that the power under Art 142 has certain limitations and fetters.

- It held that while exercising power under this article:

- The court should not ignore the substantive rights of a litigant under the existing law.

- The power could not be used to supplant substantive law applicable to a case.

- Express statutory provisions cannot be ignored.

- It cannot exercise the jurisdiction in violation of the statute.

- It clarified that no court has competence to issue a direction contrary to the law.

- The courts are meant to enforce the rule of law and not to pass orders contrary to law.

- In 2006, the apex court ruling by a five-judge Bench in ‘State of Karnataka vs Umadevi’ clarified that complete justice under Article 142 means justice according to law and not sympathy.

Why in News?

- The Corporate Affairs Ministry (MCA) has notified the introduction of the ‘Leniency plus’ regime, which is already recognised in jurisdictions like the UK, US, Singapore and Brazil.

- This will pave the way for the Competition Commission of India (CCI) to roll out a new Cartel detecting tool that is expected to revolutionise Anti-Trust enforcement in the country.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- What is Cartelisation?

- What is Leniency Plus?

- Significance of the Leniency Plus Regime

What is Cartelisation?

- According to the CCI, cartelisation is a practice in which a group of competitors (manufacturers, sellers, distributors, etc.) form an agreement to limit competition.

- It reduces output while increasing prices, driving customers out of the market (if they refuse to pay a higher price) and unknowingly transferring wealth (if they want to pay).

- A cartel protects its members from full market exposure, which reduces costs while harming overall economic performance and innovation.

- Cartels vs monopoly: A monopolist completely dominates a particular market (since there is no rival), whereas cartels are formed (with the goal of limiting competition) to dominate the market.

- The Competition Act of 2002 intends to foster and preserve market competition, safeguard consumer interests, and secure market players’ freedom to trade.

- It created the CCI to eliminate practices that harm market competition.

- The Competition (Amendment) Act 2023 codifies cartel facilitators’ liabilities. The CCI can now impose fines of up to 10% of an enterprise’s entire global turnover.

What is Leniency Plus?

- Leniency plus is a proactive antitrust enforcement strategy aimed at attracting leniency applications by encouraging companies already under investigation for one cartel to report other cartels unknown to the competition regulator.

- The benefit of such disclosure would be a reduction of the penalty in the first cartel for the individual sharing the information, without prejudice to the company receiving a lower penalty for the newly disclosed cartel.

- While the Competition (Amendment) Act 2023 provides a framework for CCI to deal with leniency or lesser penalty applications, it until recently did not recognise leniency plus.

Significance of the Leniency Plus Regime:

- The CCI had (in October 2023) issued draft Lesser Penalty regulations.

- The draft regulations offer leniency applications in an ongoing cartel inquiry the incentive to disclose the details of another unrelated cartel.

- Under leniency plus, an applicant who has filed an existing lesser penalty (LP) application, and who makes full, true and vital disclosures in respect of the existence of a second cartel is eligible –

- To receive an additional reduction in monetary penalty of up to 30% in the first cartel.

- The applicant would also get a reduction of penalty of up to or equal to 100% in respect of the newly disclosed cartel.

- A leniency plus regime is expected to further incentivise applicants to come forward with disclosures regarding multiple cartels, thereby enabling the CCI to save time and resources on cartel investigation.

- This will give the CCI the requisite tools to focus their enforcement efforts at successfully prosecuting cartels which have a direct impact on the economy and consumer welfare.

Why in News?

- The Supreme Court has decided to examine if a divorced Muslim woman is entitled to a claim of maintenance under Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) against her former husband.

What’s in Today’s Article?

- Background (Context, News Summary)

- About Muslim Women Act, 1986 (Key Provisions)

- About Section 125 of CrPC

- Court’s Prior Judgements

Background:

- A Muslim man had challenged a Telangana High Court direction to pay ₹10,000 interim maintenance to his former wife.

- He contended that maintenance in this case will instead be governed by the provisions of the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986.

- He told the Supreme Court that the Telangana HC had failed to appreciate that the provisions of the 1986 Act, which is a Special Act will prevail over the Provisions of section 125 CrPC which is the general Act.

- The Supreme Court while hearing the petition by the Muslim man observed that the 1986 Act does not say that a divorced Muslim woman cannot file a petition under Section 125 of the CrPC, 1973.

- The Court has reserved decision on the question as to which of these two laws would prevail.

About Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986:

- The 1986 Act is a religion-specific law that provides for a procedure for a Muslim woman to claim maintenance during divorce.

- It was enacted to essentially nullify the Supreme Court’s 1985 decision in the case of Mohd. Ahmad Khan v. Shah Bano Begum which upheld a Muslim woman’s right to seek maintenance from her divorced husband under Section 125 of the CrPC.

- The verdict was, however, perceived by many to be an affront to religious personal laws.

- Section 3 of the 1986 Act guarantees the payment of maintenance to a divorced Muslim woman by her former husband only during the period of iddat.

- Iddat is a period, usually of three months, which a woman must observe after the death of her husband or a divorce before she can remarry.

- Such an amount shall be equal to the amount of mahr or dowry given to her at the time of her marriage or any time after that.

- After the completion of the iddat period, a woman can approach a first-class magistrate for maintenance in case she has not remarried and is not in a position to take care of herself financially.

What is Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC)?

- Section 125 of CrPC lays down a Secular law for the maintenance of Wife, Child or Parents.

- It is a legal provision that allows certain categories of individuals to claim financial support from their spouses or children, as the case may be, in the event they are unable to maintain themselves.

- This section helps giving monetary assistance to the vulnerable avoiding situations like Vagrancy and Poverty.

Prior Judicial Precedents:

- The Allahabad High Court, in multiple judgments, has reaffirmed a divorced Muslim woman’s right to claim maintenance under Section 125 of the CrPC even after the completion of the iddat period as long as she does not marry.

- In Mujeeb Rahiman v. Thasleena (2022):

- A single judge of the Kerala High Court observed that a divorced Muslim woman can seek maintenance under Section 125 of the CrPC until she obtains relief under Section 3 of the 1986 Act.

- Such an order will remain in force until the amount payable under Section 3 is paid.

- Noushad Flourish v. Akhila Noushad (2023):

- A Muslim wife who effected her divorce by the pronouncement of khula (divorce at the instance of, and with the consent of the wife) cannot claim maintenance from her husband under Section 125 of the CrPC.

Why in news?

- One of the three priority areas agreed upon during India’s G20 presidency in 2023 was accomplished as the World Health Organization (WHO) launched the Global Initiative on Digital Health (GIDH) through a virtual platform.

What’s in today’s article?

- Digital health

- Global Initiative on Digital Health (GIDH)

What is digital health?

- Digital health refers to the use of technology, such as mobile devices, software applications, and other digital tools, to improve health and healthcare delivery.

- Basically, it is a multidisciplinary concept that includes concepts from an intersection between technology and healthcare.

- It encompasses a wide range of technologies and services, including telemedicine, electronic health records, wearable devices, health information exchange, and more.

- India’s CoWIN, UNICEF’s RapidPro and FamilyConnect etc. are few notable examples of digital health initiatives.

- The real-time information platform, RapidPro, is a core solution in UNICEF’s digital health portfolio.

- UNICeF’s FamilyConnect sends targeted life cycle-based messages via SMS to pregnant women, new mothers, heads of households etc.

Why is digital health important?

- Empowers patients

- Digital tools are giving providers a more holistic view of patient health through access to data and giving patients more control over their health.

- Hence, it empowers patients to make better-informed decisions about their own health.

- E.g., wearable devices can monitor vital signs and provide real-time feedback to patients and clinicians.

- Treatment of disease

- Digital health tools provide new options for facilitating prevention, early diagnosis of life-threatening diseases, and management of chronic conditions outside of traditional health care settings.

- Other benefits

- Reduce inefficiencies; Improve access; Reduce costs; Increase quality, andMake medicine more personalized for patients.

- Support overall universal health coverage targets

- Digital health is a great enabler in delivery of healthcare services and has the potential to support overall universal health coverage targets.

- This is because it can ensure availability, accessibility and affordability, and equity of health services.

- For example, telemedicine allows patients to connect with healthcare providers remotely.

- Digital health is a great enabler in delivery of healthcare services and has the potential to support overall universal health coverage targets.

What are the challenges of digital health?

- Equitable access

- Universalization of digital health and enabling of equitable access to healthcare services across the world, particularly for low- and middle-income countries is challenging.

- The issue of accessibility becomes more daunting against the backdrop of low digital literacy and low-level of internet penetration.

- Ethical Challenges related to privacy, security and data ownership

- The increasing digitization of healthcare and the growth of mobile and IoT devices as data collection tools raises many ethical issues.

- One commonly recurring theme relates to the exact nature of the role of consumer tech companies, such as Amazon, Apple etc. who have all entered the digital health domain.

- Such companies offer solutions for collecting, storing and analysing health data which raises issues relating to privacy, data protection and informed consent.

- Analysts also raise ethical concerns relating to data ownership.

- Ethical challenges related to regularisation of digital health technologies

- The growth of apps and technologies developed for a consumer market blurs the lines between what is medical and non-medical devices.

- Hence, it raises ethical challenges relating to how to regularize such technologies.

- Data management

- Due to the massive amounts of data collected from a variety of systems that store and code data differently, data interoperability is an ongoing challenge.

What is GIDH?

- GIDH is one of the key deliverables of India’s G-20 Presidency.

- It will consolidate the evidence and amplify recent and past gains in global digital health while strengthening mutual accountability to enhance the impact of future investments.

- GIDH will be a WHO Managed Network (“Network of Networks”) that will promote equitable access to digital health.

- It will do so by sharing digital goods and knowledge.

- The GIDH will ensure inclusivity, integration, and alignment of healthcare goals by not leaving anyone behind.

What are the aims of GIDH?

- ALIGN efforts to support the Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025;

- SUPPORT quality assured technical assistance to develop and strengthen standards-based and interoperable systems aligned to global best practices, norms and standards;

- FACILITATE the deliberate use of quality assured digital transformation tools that enable governments to manage their digital health transformation journey.

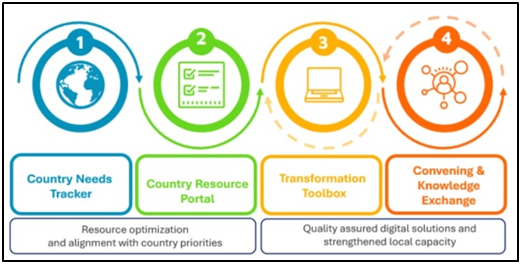

What are the pillars of GIDH?

- It will have four pillars:

- investment tracker; ask tracker to track technologies the countries need; a library of available digital tools, and a platform for knowledge-sharing to implement these technologies at scale.

What are the strategies to be employed by GIDH?

- The GIDH will bring countries and partners together to achieve measurable outcomes by:

- developing clear priority-driven investment plans for digital health transformation;

- improving reporting and transparency of digital health resources;

- facilitating knowledge exchange and collaboration across regions and countries to accelerate progress;

- increasing technical and financial support to the implementation of the Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025 and its next phase.